The Male Mind, the Shadow, and Becoming Tony Soprano

What HBO's Iconic Antihero Reveals About Good, Evil, and the Path to Wholeness

This summer marked my fourth time finishing the Sopranos. Yes, my fourth time.

Fresh off finishing The Good Place, my wife and I were riding the momentum of great shows. "Let's commit to the Sopranos,"—we agreed. A boyish ecstasy ignited within me – I knew what this journey meant and was excited to find out what would be different about it this time around.

It was my wife's first time watching the show, and I was giddy to share its excellence with her. Each episode's run time feels like the snap of a finger, immersing us in a meaningful ride together. I've come to realize that any experience that compresses time to but a moment hints at something fundamental about the nature of humanity.

I contemplated writing a piece about the show but decided against it despite a moderate feeling to do so. I thought, "Maybe I'll write one after the fifth watch..."

Reading Catherine Shannon's piece, "The male mind cannot comprehend the allure of Tony Soprano," sparked my urge to write this. Her humorous take had me hooked, though I found myself enamored by Tony Soprano rather than repulsed or confused by him. She highlights two extremes of men who fail to grasp Tony's appeal, which I’ll now extrapolate on: the virtue-signaling "male feminist" obsessed with dismantling the tyrannical patriarchy, and the Alphamaxxed-Gigachad guzzling nutrient-dense breast milk and spending four hours a day at the gym to gain 14 mm on his biceps.

I wanted to write this not to disagree but to explore what I think allows the male mind to understand Tony's allure, which is interconnected with developing the characteristics described in Catherine's writing.

This piece is for men who not only understand Tony Soprano's allure but are introspective enough to recognize that Tony lives within us all.

HBO's white noise-to-hum introduction has become inseparable from the opening that forever echoes in my ears: Alabama Three's Woke Up This Morning. It perfectly sets the tone—Tony's white Escalade emerges from the Lincoln Tunnel in Weehawken, New Jersey, gold glinting on both wrists, a cigar perched between his fingers as he rolls into his curved driveway.

This time around, I found myself questioning if Tony deserved more credit for trying to be a good guy or if I was tricked by a sociopath's charm. It's likely the latter, and I'm in good company.

When we talk about characters like Tony Soprano in a positive regard, we tend to make the proper disclaimer, "Yes, I know his murderous, manipulative, emotionally abusive, explosive, infidelity, and racism is wrong and evil.”

I think we do this to ensure that by talking about Tony's positive characteristics, we don't indicate we agree with the negative ones. "I can never do those things!" one would say. This signaling casts away the bad characteristics so we can talk about the good, typically without realizing that those evil characteristics are also human. That means that we're all capable of the actions Tony's capable of.

We often view evil as the opposite of good, but the two are inextricably linked. By recognizing this, we can examine those traits within ourselves and choose to redirect their energy toward positive ends—a choice Tony fails to make through improper integration.

Starting in the pilot episode, the Sopranos invites us into something television didn't consistently display before. Sitting across from his therapist, Tony breaks into tears upon the realization that his panic attack—on the surface induced by the fleeing of ducks who briefly lived in his pool that he took an obsession with—was an unconscious projection of his fear of his family falling apart. The Sopranos is a portal to something most don't acknowledge: people we regard as evil still have a positive humanity, albeit more mute than typical.

Tony's therapy sessions, juxtaposed with his horrific acts, offer a window into humanity's dual nature—a reflection into our own shadow.

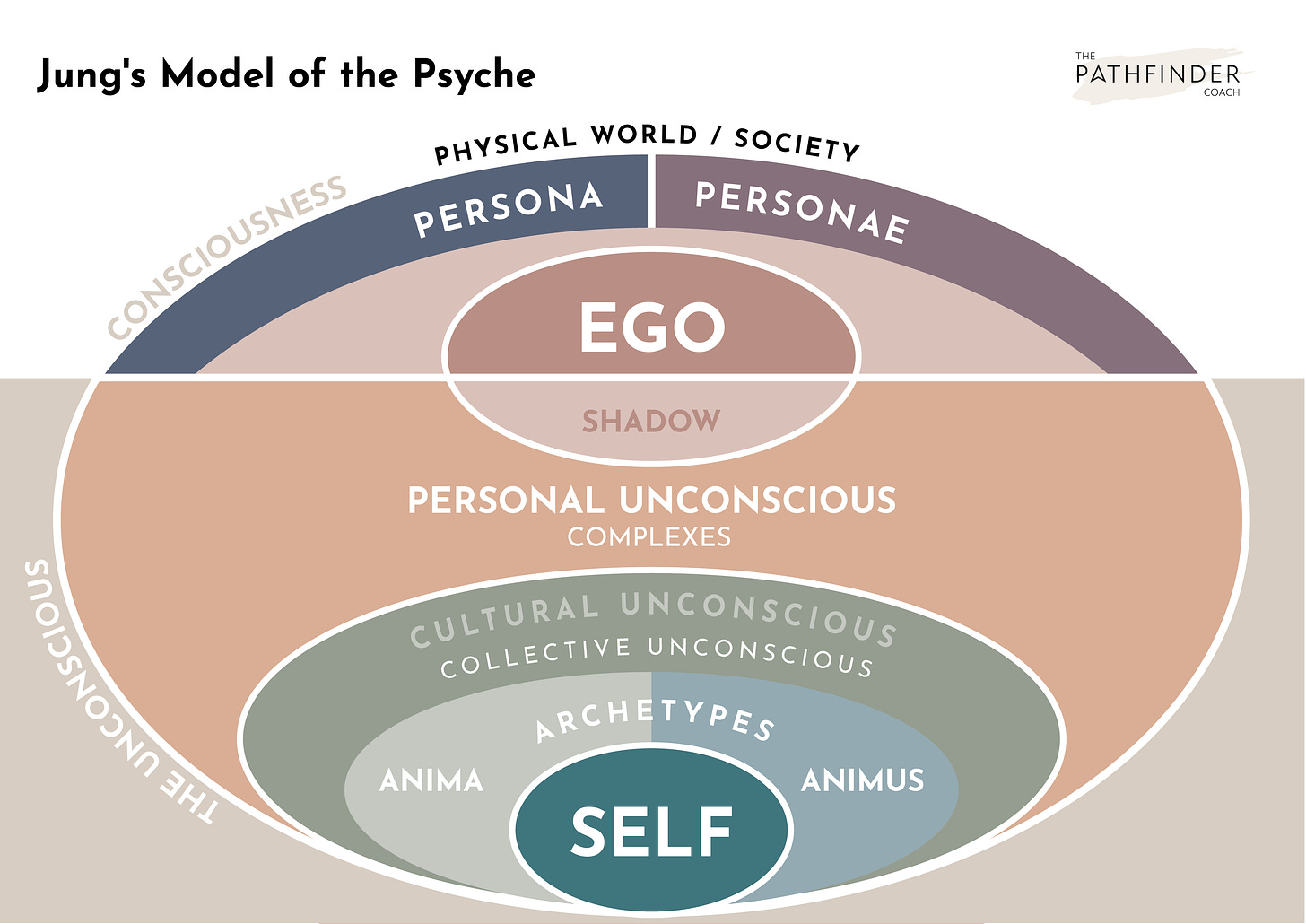

Carl Jung, founder of Analytical Psychology and one of the most brilliant thinkers of the 20th century, redefined Freud's psyche with a more nuanced framework. In his conception, Jung laid out what he called the shadow—the parts of our personality that are repressed, hidden, or denied, often because they conflict with our conscious self-image. The concept is nuanced; it doesn't simply mean "all the bad stuff," but rather, that which you look away from and refuse to integrate within yourself.

A Jungian view is that everyone harbors the capacity for all aspects of human experience—even the darkest horrors. This is an unsettling but vital truth.

Marie-Louise von Franz, a well-known student of Jung, explored the Shadow in Man and His Symbols, writing:

"Through dreams, one becomes acquainted with aspects of one's own personality that, for various reasons, one has preferred not to look at too closely… The Shadow is not the whole of the unconscious personality. It represents unknown or little-known attributes and qualities of the ego-aspects that mostly belong to the personal sphere, and that could just as well be conscious."

Tony Soprano bangs on the door of the male mind, and in our unmasculine era, most don't answer. Defense mechanisms propagate to protect the viewer from their refusal to look inward at their inadequacies.

"Everything that irritates us about others can lead us to an understanding of ourselves." (Jung, Memories, Dreams, Reflections)

For most, irritation is easier than acknowledgment; facing and accepting the dark impulses within is challenging and tricky.

"The shadow is a moral problem that challenges the whole ego-personality, for no one can become conscious of the shadow without considerable moral effort." (Jung, Aion: Researches into the Phenomenology of the Self)

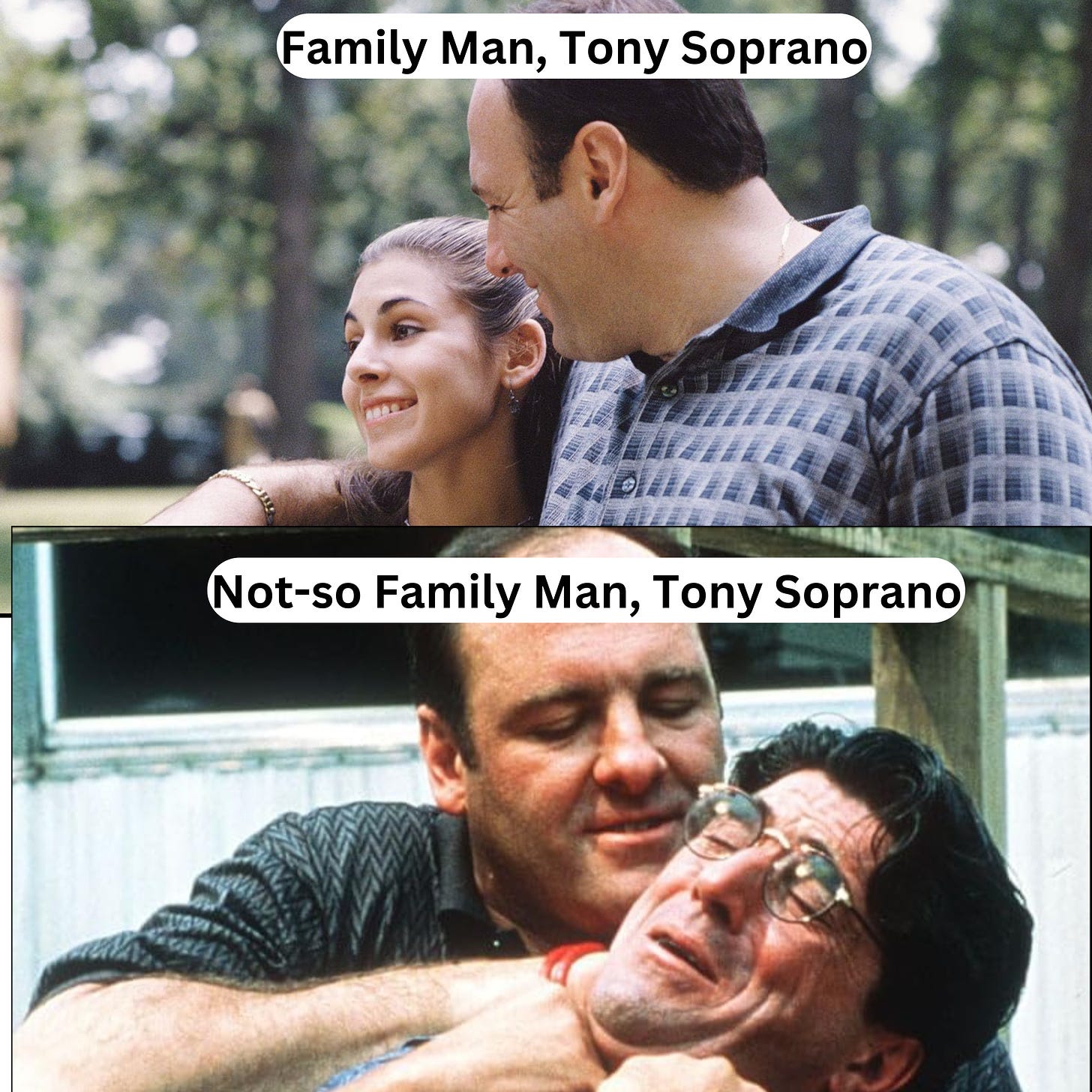

Catherine points out Tony's collection of attractive traits: competence, a genuine attraction for women, safety, loving attentiveness, lightheartedness, charisma, charm, and courage.

Tony embodies these positive characteristics partly because he has integrated parts of himself—albeit improperly—that allow the expression of those traits. An example is the impulse toward violence—raw, primal energy. Jung would argue that while the literal expression of the energy as violence is unacceptable (and where Tony fails), the psychic energy behind the impulse—passion, intensity, and primal force—can be redirected toward positive ends.

Traits like selfishness, for example, if repressed, lead to narcissism. Conscious selfishness can foster necessary self-care and reflection, boundary-setting, and personal growth.

One thing often misunderstood in our society is that good and evil aren't binary opposites. Our cultural narratives often paint good and evil as separate forces—heroes and villains. However, Tony Soprano shows us that these impulses are intertwined and recognizes that complexity is essential for personal growth. In fact, integrating the capacity for evil might be a prerequisite for greater moral virtue. Nietzsche's insight underscores this idea,

"The great epochs of our life come when we gain the courage to rechristen our evil as what is best in us” (Beyond Good and Evil)

Tony's admirable qualities—like courage—emerge from his integration of darker impulses. Where Tony goes wrong is by using psychic energy toward destructive ends, such as channeling his violent impulses into real-world harm. The energy behind Tony's darker traits, such as his violence, could fuel moral virtues if properly channeled.

On the positive side, he is loving, carefree, fun, witty, and funny. The carefree attitude is born from his integration of exercising control and expressing his power drive. Tony doesn't hold back on his wit and humor, which comes from integrated verbal expression. He speaks as he sees it without fear of being attacked because he will stand his ground.

Throughout The Sopranos, viewers watch Tony grapple with business and family problems while oscillating between his positive and negative traits, sometimes solving his problems using the extremes of his darkness.

Tony's inner struggle plays out vividly in Season 1, Episode 5, "College." Tony takes his daughter Meadow on college tours when he spots Febby, a former mobster now in witness protection. Torn between his mafia code and his role as a father, Tony contemplates whether to kill Febby while evading Meadow's probing questions about his involvement in the mafia. He sneaks around to gather intel from his nephew Christopher, deepening the web of deceit.

Meanwhile, in New Jersey, the neighborhood priest, Father Intintola, visits the Sopranos household and Carmella and him share a night that increasingly grows intimate, and the priest ends up spending the night after drinking too much. Carmella grapples with her own feelings of loneliness and the lies in her marriage, especially after receiving a call from Tony's therapist—who Tony had falsely described as a man—canceling an appointment.

What better episode for viewers to confront the darkness within themselves? Will Tony tell Meadow the truth? Will he spare Febby or uphold his code? How does Carmella handle the revelation of Tony's deceit and her own actions with Father Intintola? "College" challenges us to consider the complexities of honesty, loyalty, and the moral choices that define us.

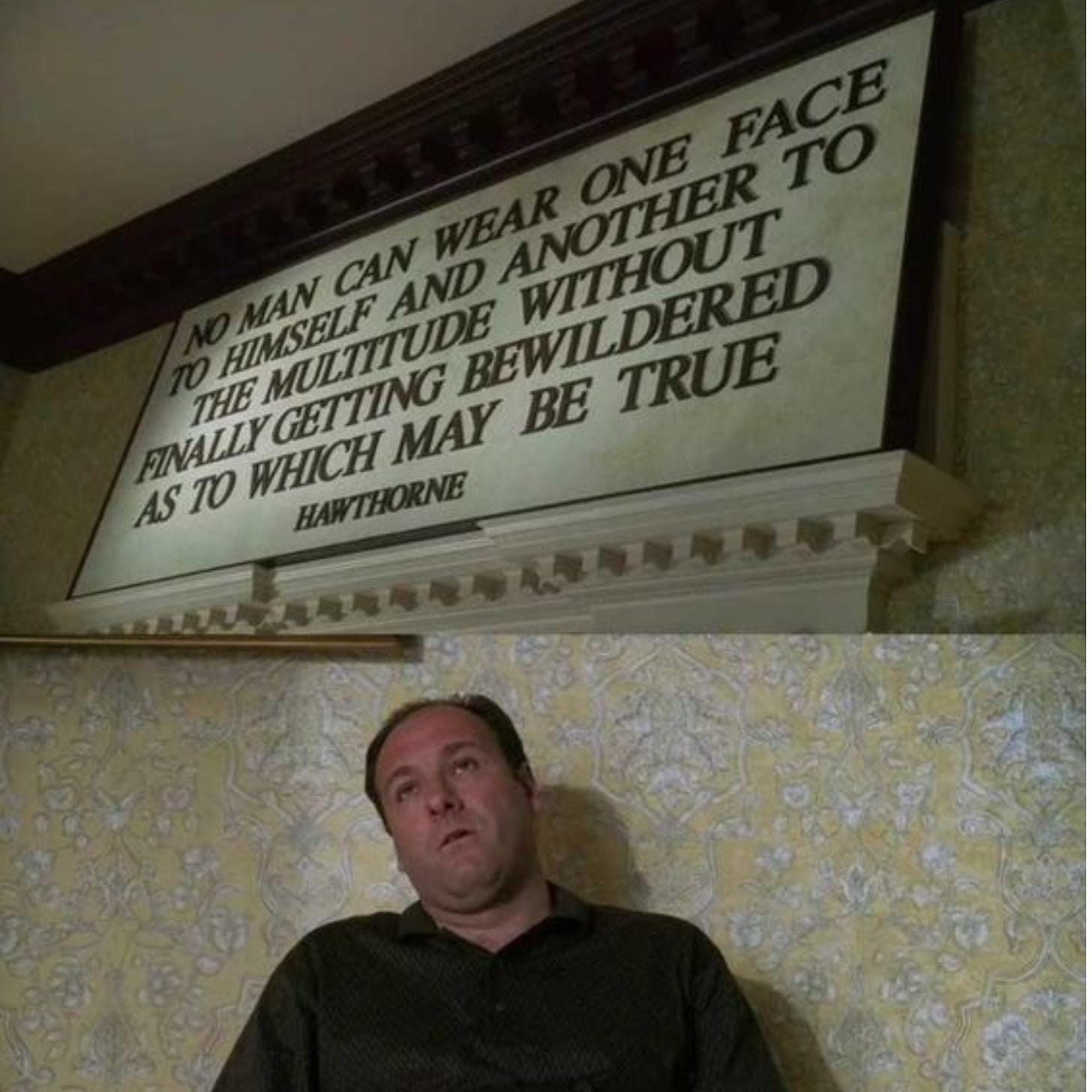

Tony ultimately kills Febby, fabricating a story to Meadow when she notices the cuts on his hand and the sand from the scene of the crime. While waiting for Meadow to finish her last college interview, Tony sits down, and both he and the viewer are hit with a moment of stark contemplation as he peers up at the following Hawthorne quote:

The Hawthorne quote looms over Tony as a mirror of his fractured self. By killing Febby and lying to Meadow, Tony reveals the dangers of inappropriate Shadow integration. His violent impulses, unexamined and unchanneled, lead him to destruction rather than resolution. His deceit, meanwhile, deepens the divide between the father he wants to be and the mobster he cannot escape.

They return home, and the oscillation from dark to funny kicks in as Carmella tells Tony that Father Intintola spent the night and they were alone. The best writing can't emphasize James Gandolfini's delivery, so I'll leave the video here.

The Sopranos portrays a man with significant flaws yet possesses positive qualities. Tony is given many chances to walk a path of redemption and stop the evil acts he commits. I longed for him to surface from the darkness his life is surrounded by, hoping he could arise from the depths that consume him.

Ultimately, he doesn't. This left me with a question: had my brain been hijacked by a charismatic sociopath, or was I drawn by a hope of redemption—longing to redeem a self that I might have lived if I'd been born into his world?

In watching Tony's arc throughout the series, we can either try to understand or cast him off as a 'bad' guy and enjoy the ride. Either is fine. It does take effort to contend with the dark parts of you, and sometimes, it isn't the right moment in life to do so. But doing so will expand one's consciousness scope and make one more whole.

The male mind that cannot understand the dangers in Tony doesn't understand this in themselves, which makes them far more susceptible to acting it out unconsciously—highly unattractive, indeed.

The Sopranos has always felt like the perfect show to me. It reflects all aspects of human nature, displayed in familiar social contexts—Tony as a father, husband, friend, brother, uncle, and nephew. Taking the journey with him as he navigates his decisions often caught me by surprise, challenging me to empathize with him and consider how I might respond in similar situations.

Ultimately, Tony Soprano is both a cautionary tale and a mirror. His journey invites us to grapple with our own darkness, challenging us to confront the impulses we might rather ignore. By exploring his duality, we not only better understand his allure but also uncover the truth of our humanity—that good and evil, light and shadow, are inseparable parts of the whole.

While Tony sometimes emulates courage, he often chooses the easier path, making others' lives worse with his choices—an act of cowardice. Most of us aren't born into the conditions Tony endured, but as we walk our own paths and seek truth, we inevitably confront the evil characteristics within and without. The extremes of our positive traits are inexorably linked to the negative ones. Recognizing this, we can strive to harness them for good rather than destruction.

If the male mind cannot comprehend Tony's allure, perhaps it has not yet comprehended itself. To understand Tony is to understand the good and evil within us all. And that's what makes his story timeless.

Until next time

Take care of yourself, everyone

Dom